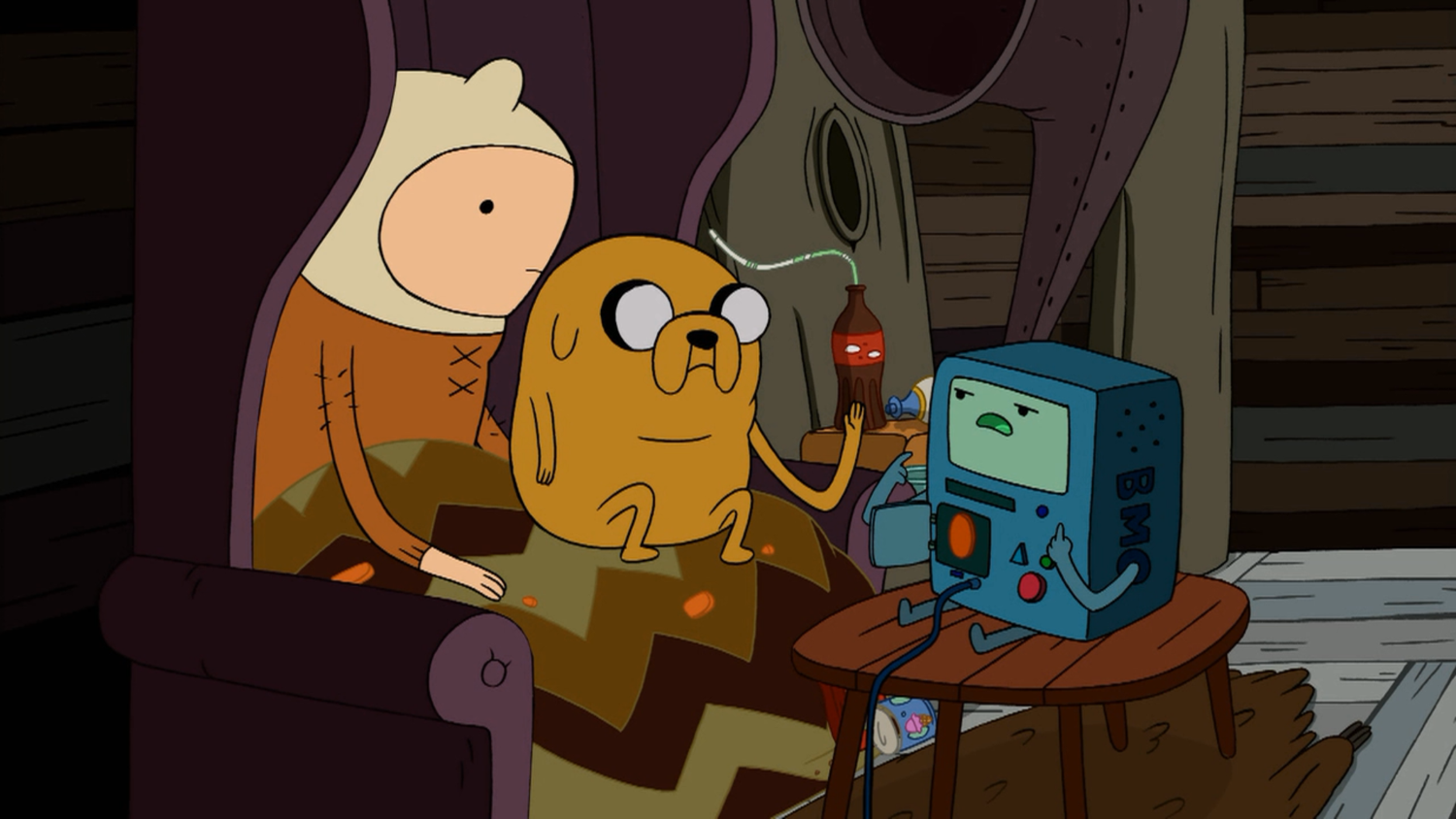

When Adventure Time viewers first meet BMO, Finn and Jake's robotic friend and roommate is serving duty as a gaming console. In "Business Time" (season 1, episode 8; see Figure 1), Finn and Jake thaw out a group of strange businessmen who at first improve and then later take over the duo's heroic exploits. No longer answering the calls of embattled princesses or other creatures, Finn and Jake spend their time in their treehouse, playing video games on BMO. In this initial cameo, BMO is unspeaking, a stylized, anthropomorphized game system. While this first introduction to BMO makes clear the character's primary or presumed function, in subsequent episodes BMO is developed further and is shown participating in adventures, intervening in conflicts, and expressing individualized desires and interests.

Figure 1: Jake plays a game on BMO in "Business Time," the first episode in which BMO appears

However, even as BMO is revealed as a rich character with a complex inner life, the console continues to serve practical, tool-like functions for Finn and Jake. In this way, BMO's position is complex and presents a potentially ontological tension between BMO's role as a developed, individual character and BMO's simultaneous role as a useful robot controlled by Finn and Jake. As Adventure Time develops, it becomes clear that BMO can occupy either of these roles depending on narrative necessity. But, BMO also fits into a developing discourse around domestic robots and provides insights into the complicated position of robotic helpers in daily life.

Consider, as anecdotal example, my own history with robots. In 2003, my family bought our very first robot. It was an early model Roomba that ultimately proved ill-equipped to deal with the heavily trafficked berber carpeting. Despite the little vacuum's inadequacies, we still saw in it a flash of what a robotic future might look like. We didn't name our Roomba, but we watched over it carefully and spoke of it much as we would have the household cat or dog. When the Roomba wedged itself under an antique dresser, one of us would swoop in to rescue it; "Oh no," my mother would say, "Roomba is stuck under the dresser."

Now just over 10 years later, my husband and I rely on a newer model Roomba to do a daily sweep of our living room. When we bought a new rug with scattered black stripes, we found the Roomba unwilling to deal with it; each stripe read as a precipice the Roomba dare not venture over. "Roomba's afraid of the rug," we explain to friends who've caught the seemingly bizarre behavior. While you may want to write me and my family members off as eccentrics, we aren't alone in our affection for and connection to these domestic robots. Over 80% of Roomba owners name their robots, and Roombas are not unique in winning over human affections. U.S. soldiers have been known to mourn bomb-disposal Packbots. There is an intimacy to our relationships with the machines that serve us.

And, science fiction provides innumerable examples of imagined robot friends and family members. In Ray Bradbury's "I Sing the Body Electric," first the 100th episode of The Twilight Zone and later a short story by the same name, a robotic grandmother joins the household of a widowed father of three, endearing herself to the children. The Star Wars universe has its own charming robots in R2D2 and C3PO. On The Jetsons, the household's robotic maid, Rosie, is woefully out of date, but the family steadfastly refuses an upgrade: they love her too much. In Terminator 2: Judgment Day, the cyborg played by Arnold Scharzenegger, made obsolete in the future by the evolution of liquid metal cyborgs, is now tasked with protecting John Connor against one of these more advanced cyborgs. Obsolete technologies sometimes seem cuddlier, and Sarah Connor goes so far as to say that the outdated cyborg is the father her son John always needed. While science fiction also has given us numerous examples of robots and artificial intelligences run amuck--as in 2001: A Space Odyssey, TRON, and of course the Terminator franchise--it is this imaging of friendly, domesticated robots that seems most relevant to an emerging culture of daily robotics, one marked by Roombas decorated with googly eyes and called by names like "Rosie" and "Roswell."

Roombas serve the needs of their owners, but they also can appear to take on their own lives as in my current Roomba's seeming fear of the rug's black stripes. And, it is often these kinds of quirks, which are at some level a failure of intended function, that we become invested in the robots' perceived lives. Domestic robots promise service or companionship without the messy complications of human autonomy. More than a dozen robotic dogs have been released to the consumer market, attempting to offer the charm and companionship of their flesh-and-blood brethren without the messy physical needs or tendency to chewing. The iconic Tamagotchi digital pets of the late 1990s offered disembodied pet ownership for children of parents unwilling or unable to contend with the obligations posed by a dog or cat. The pixelated pets may have seemed a poor substitute, but they were so beloved by children that many schools enacted bans and virtual graveyards sprung up on the web.

Although inhabiting the post-apocalyptic wonderland of Adventure Time, BMO at times seems removed only by degrees and technical capabilities from these contemporary robotic or computerized companions. BMO has a primary function as a game console, but fulfills numerous other roles throughout the show. That BMO's gender is fluid -- BMO is at times referred to as "she" or "he" depending on the narrative -- speaks to the way the character's identity can change based on context, narrative needs, or perhaps even personal expression. While some episodes give the sense that BMO is subservient to Finn and Jake, in others BMO is shown as disruptive or at least disobedient, a puckish presence in the periphery of Finn and Jake's friendship or a would-be guardian for the young heroes.

In the episode "Incendium" (season 3, episode 26), Jake tasks BMO with looking after a heartbroken Finn. BMO readily agrees to the role of caretaker, saying "If anyone tries to hurt Finn, I will kill them." Later, as Jake checks in on Finn using a small projector, we see Finn from BMO's perspective telling BMO to go away. BMO does not leave, but instead creeps up on Finn saying "Duck, Duck, Duck, Goose" and presumably goosing Finn. "Incendium" shows BMO in many of the roles the character fulfills. BMO is fiercely loyal to and protective of Finn, but also willing to tease him, even as Finn wallows in misery; at the same time, BMO serves a tool-like purpose for Jake, who uses BMO's integrated camera to check in on the lovesick Finn.

BMO is loyal not only to Finn and Jake as individuals, however, but also to their friendship. For example, in "Video Makers" (season 2, episode 23), BMO follows Finn and Jake as they attempt to shoot their own movie for film club using an old camera. Throughout the episode, the pair fight over what footage is worthwhile and what focus the movie should have. They finally turn to BMO to resolve the conflict, handing over the footage to edit with instructions to only pick the best scenes. BMO avoids directly answering their questions, and so when the movie is shown, neither Finn nor Jake know what the movie will be like, and in fact continue to argue over whose footage was best and most likely to be featured. Instead, however, BMO has cut a movie of their own design. The movie features scenes of Finn and Jake with BMO's original song stressing the importance of their friendship and asking that they forgive one another. By making the movie, BMO makes an essential intervention but also defies the instructions given by Finn and Jake. As in other episodes, BMO demonstrates a level of autonomy that far exceeds what might have been assumed based on the character's early, often speechless, appearances. Indeed, in episodes like "Video Makers," BMO is revealed not as a household device, but as a thinking, feeling entity with independent desires, preferences, and even hobbies.

In "The Creeps" (season three, episode twelve; see Figure 2) Finn tells BMO to evaluate the party guests with his ghost-detecting equipment to find out who the ghost is. BMO pulls out some equipment and goes quickly to work, but later admits having no ghost-detecting gear: "I just like taking nice pictures." BMO also likes dancing, as shown in several episodes, and expresses disdain and affection for various characters. In particular, BMO responds a bit thornily to the efforts of Neptr (Never-Ending Pie Throwing Robot) to spark a friendship. In "BMO Noire" (season 4, episode 17), BMO rejects Neptr's suggestion of friendship, saying "I am not like you," and in the opening of "Furniture and Meat" (season 6, episode 8), BMO and Neptr are going to play act Robin Hood, but the pair instead fight over BMO's insistence that Neptr be the villain and not Robin Hood's friend.

Figure 2: BMO photographs the other party guests in "The Creeps."

The appeal of robots is so often the problems they won't cause. The robotic cat never claws the sofa. The robotic grandmother never dies. But, the very appeal of BMO is the extent to which the character causes problems and defies the boundaries of what we might assume possible. BMO is loyal, but BMO is also just irreverent enough to be interesting, something other than a mindless drone but not something so autonomous as to be threatening. BMO may tease, but not lead an uprising. In this, BMO is more like the rugphobic Roomba than the desperate, murderous replicants of Bladerunner. We want our robots human, but we want them to love us, to console and comfort us.

And, BMO sometimes fulfills this function, a consoling console, but BMO is a nurturer who can be literally shut off or ignored. In "Guardians of Sunshine" (season 2, episode 16), for example, BMO warns Finn and Jake against entering the game in the "Main-Brain-Game-Frame" but rather than heed BMO's advice, the pair wait until BMO is asleep to enter the game. In the course of the episode, they release the game's monsters into the real world, where they turn first on BMO, who they view as their captor, and then on Finn and Jake. In this episode as in "Video Makers," it is clear that BMO works towards Finn and Jake's best interests, but is sometimes thwarted in efforts to protect the pair as they don't always want to be protected or cared for.

Figure 3: BMO scolds Finn and Jake in "Guardians of Sunshine."

BMO's position in the tree fort and in Finn and Jake's lives is complicated. The console is more than a device, but perhaps less than a roommate. BMO is perhaps, almost a loyal servant, as shown in episodes like "The New Frontier" (season 3, episode 18) in which BMO is used as a walking serving tray to deliver Jake's pizza ice-cream sandwich--a duty BMO seems displeased with yet still performs. And, perhaps it is this combination of service even in the face of displeasure that most defines BMO and is at the root of viewers' affection for the charming robot. Finn and Jake can become in feedback loops of human--or at least humanoid, in the case of canine Jake--emotion that BMO is able to disrupt and resolve specifically because BMO is simultaneously more empathetic and less emotional. The robot is not beholden to the kinds of petty grudges or wounded pride that so often would prevent resolution. BMO as intermediary is a means of disrupting negative emotional conflicts and reestablishing and healing vital connections. In this way, BMO is a third party in the relationship between Finn and Jake, serving whatever role may be necessary to the preservation of their bond.

BMO has, alongside Adventure Time's other characters, become iconic, readily available as diverse items like plush toys and pillows, cell phone cases and hooded sweatshirts, and even a periphery for the iPad mini that transforms the tablet into a facsimile of BMO as console. BMO is beloved by viewers, and that resonance is complicated by BMO's own strange and sometimes contradictory characteristics. The use of BMO as a case for real life technologies speaks to efforts to anthropomorphize and personalize those same technologies. A cell phone with the face of a console with a face is just an iota friendlier than the standardized white plastic case even as those same cell phones increasingly speak to us with humanized voices--an idea explored extensively in Spike Jonze's 2013 film Her in which a lonely man falls in love with his computer's artificially intelligent operating system. Perhaps romantic love from a computer system is too much to ask for, something too far from our current expectations of technological intimacy. But, the robot servants that (mostly) wordlessly vacuum our carpets and the phones that calmly tell us how best to get to the grocery store are already here. When we imagine a technological future, when we imagine robots that might provide not romance, but a kind of care and loyalty that many of us are desperate for, we might imagine something like BMO, with our best interests always at heart, but just defiant, just quirky enough that we can imagine that care is given by choice.